Longread. By Richard Clements & Augusto Bravo.

Fall 2024

In their 2010 piece, ‘Towards an Emancipatory International Law: The Bolivarian Reconstruction’, Mohsen Al Attar and Rosalie Miller posited the Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América or Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas as a potentially radical ‘alternative international legal regime’ (at 352). Grounded in what they regarded as the emancipatory potential of the Bolivarian revolution across countries including Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador, they saw the Alliance (‘ALBA’) as having the potential to rekindle the foundering Third Worldist project in/for the 21st century. Rather than seeking to respond directly to Al Attar and Miller’s proposition regarding ALBA and the fate of the Bolivarian Revolution, we seek to place that common call for radical, emancipatory alternatives alongside two images. These two images are photographs we took while visiting family in Venezuela in March 2024. They offer two distinct comments on, and styles of, Bolivarian international law.

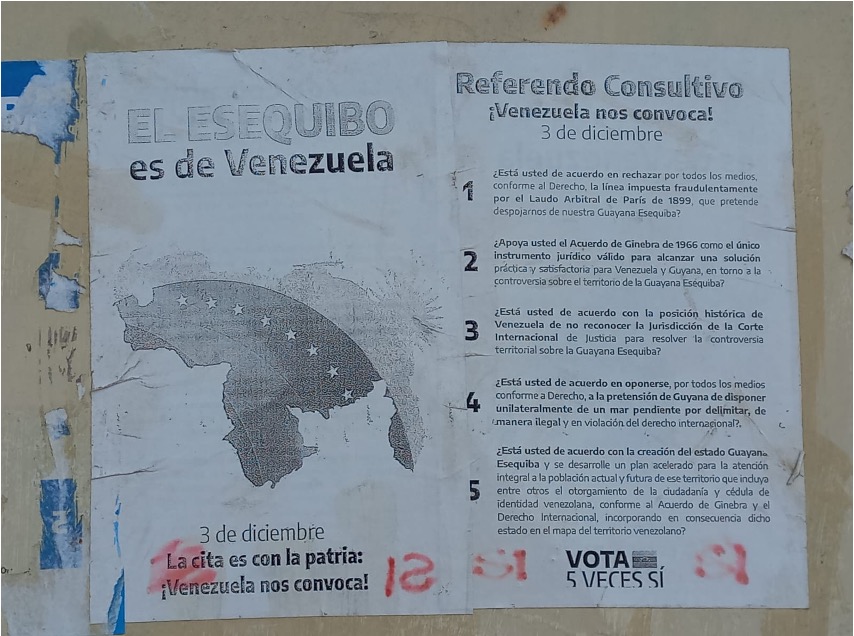

The first image is a referendum poster, pasted hastily on the door of an abandoned house in the seaside fishing village of Choroní, on the north coast of Venezuela. Because we, as international jurists, are textual creatures, it is difficult not to immediately begin reading the numbered paragraphs on the poster. To that end, the poster asks leading questions (e.g., ‘do you agree…?’, ‘do you support…?) related to the December 2023 referendum held by the Venezuelan government to consult on the acquisition (or annexation) of the Esequibo region. The region is the subject of a long-standing territorial dispute between Venezuela and British Guyana, and officially forms over half the landmass of the latter. Interestingly, the text of the poster recounts the twists and turns of this international legal dispute to its hypothetical viewer. The poster claims to Venezuela historic title over the region and poses the government’s summary arguments against its detractors.

Such a pre-emptive, guarded style is a hallmark of Venezuelan articulations or ‘Bolivarian’ international law, both domestically and globally. It cites the 1966 Geneva Agreement which committed Venezuela and British Guyana to finding a peaceful settlement to their dispute. This is claimed to annul the 1899 arbitral award that separated Venezuela from the Esequibo region along the line demarcated by the Esequibo river. The poster also rejects the International Court of Justice’s jurisdiction to adjudicate the dispute.

Behind the poster lies a subtext of additional legal doctrines

Behind the poster lies a subtext of additional legal doctrines: Venezuela’s claim to the Esequibo is derived from the colonial doctrine of ‘uti possidetis’ which established the Esequibo as a ‘Zone of Reclamation’ after its emergence out of the short-lived state of Gran Colombia in 1831. And there is an immediate political-economic context, too. Under the authoritarian regimes of Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro, the Esequibo has taken on national significance, since oil and gas deposits were discovered in the region in the last decade. The Venezuelan and Guyanan governments, as well as mining companies including the Canadian firm, GCM Mining Corp are active in 1,500 plots over a 100,000 km² area including the Potaro, Mazaruni and Cuyuni rivers.

Yet the meaning of the text, subtext and context of this referendum poster captures only part of what is happening in this image. As Stolk and Vos note, the question is not only about ‘what to look at and for, but also about how to look and see’. The form this text takes, its materiality, and its afterlife may tell us just as much, if not more, about Bolivarian international law. Indeed, that someone – presumably those who put up the poster – has sprayed a red ‘si’ (yes) at the bottom of the poster, already suggests that even its most loyal supporters appreciate the poster will not be read, or at least not in full. There is thus a performative, but ultimately superfluous, quality to the text-heavy, numbered paragraphs. This ties into the fact that the government feels obliged to (i) summarise its case for ‘si’, and (ii) offer a characteristically lengthy and unchallenged essay to its audience. When one places such a poster alongside the lengthy televised appearances of both Chávez and Maduro that remain a staple in the weekly schedule, one begins to recognise Bolivarian international law’s verbose and bombastic style.

Yet our encounter with the poster (as with the world at large) comes, as Merleau-Ponty would describe it, ‘all at once’. It is difficult to disentangle the poster from that which it now forms a part: the door on which it is pasted. This door, though not so visible in the image, is rotten; it is possible to see through it to the dark, uninhabited, caved-in room beyond. If the medium is the message, then Bolivarian international law has not fulfilled the emancipatory potential suggested by Al Attar and Miller over a decade ago. There is more, though, that extends the medium. The dwelling into which the door leads is the corner house in a row of multi-coloured, single-story houses and posadas designed in the Spanish colonial style. Some are dated: 1792.

Colonial architecture and dates of settlement, far from operating as simply the background against which the legal text is posted, is part of the viewer’s experience, and a defining characteristic of the village, which was founded by the Waikeri tribe and has historically been a gathering center of Venezuela’s black population and culture. It takes very little to recall the exactly 300 years preceding the construction of such houses as the construction of a similarly European colonial style of international law across the Americas, North and South.

The same year, 1792, Spanish settlers began to cultivate Choroní for cacao. Here, Captain Diego de Ovalle put the indigenous inhabitants of the village to work in several new plantations. Meanwhile, in the Esequibo region under dispute over two centuries later, the Dutch West India Company was establishing a colony. It becomes difficult to disentangle the connections between Spanish extraction, Dutch colonisation, and contemporary Venezuelan socialismo del Siglo XXI (‘twenty-first century socialism’). At least one way to place them together is via the multiple styles and un-styles – rhetorical and architectural – of international legal work across four centuries but localised in one town, one image.

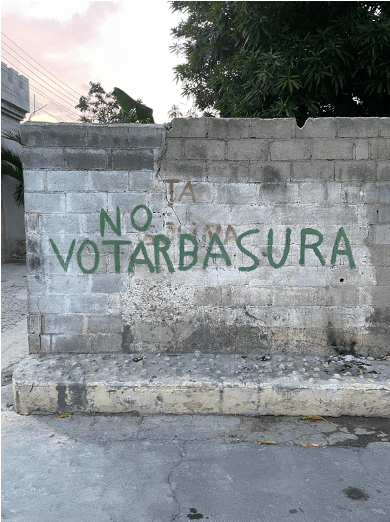

This leads to the second image, and returns us to the failed promise of ALBA. The graffiti on a collapsing wall contains two meanings in one, an experience of indeterminacy. With rubbish bags lying in the street around and no municipal sanitation service, residents have taken to spraying ‘Do not dump rubbish’ around the village. This, in itself, could be comment enough on the state of the nation.

Yet as experienced and spoken, the text may also read ‘Do not vote [for] rubbish’. The ambivalence, and unintentional irony, of this alternative slogan takes on renewed relevance in recent months, after widespread voter fraud, vote suppression and election tampering resulted in the incumbent Nicolas Maduro claiming victory for a third term (the party of which he forms a part has been in government since 1999 on an anti-neoliberal platform, yet from the mid-2000s, the country has experienced rapid economic and political decline resulting in the emigration of millions of citizens). If the government’s referendum poster captures Bolivarian international law in its official, brazen style, then the messages sprayed between residents suggests an unofficial Bolivarian international law in graffiti style.

Image credit: Richard Clements