Mark A. Drumbl and Shannon Fyfe[1]

A small municipal museum in Münster shows the breadth of German colonialism across the African continent (Figure 1). While the phenomenon was short-lived, as Germany’s claimed territories were quickly ‘lost’ through peace agreements and cession treaties with other Western states, it ran deep, leaving indelible marks. German colonialism remains underdiscussed and underremedied. The two of us spent time in one former German colony, Namibia, in October 2025. For us, Namibia’s soil and those buried underneath, and Namibia’s streets and those who currently walk them, intertwine deeply with international law and transitional justice.

Histories, Crossings, and Journeys

Namibia’s earliest inhabitants were the San peoples. The Khoekhoen (the ancestors of the Nama people) came to Namibia in the first century AD; then the Damara in the 9th century; the Ovambo in the 14th century; and the Herero (Ovaherero) in the 17th century. German rule over Namibia began under Otto von Bismarck in 1884, only to become unglued by World War I and the Treaty of Versailles. In 1920, the League of Nations issued a mandate giving South Africa the power to govern Namibia. Namibia’s territory was known as Deutsch-Südwestafrika (or German South West Africa) in German times and then as South West Africa in South African times. While under South African rule, Namibia became the site of apartheid policies as of 1948, the year in which the National Party assumed power in Pretoria.

On March 21, 1990, as the then-South African government crumbled, Namibia finally gained independence. Namibia is therefore a fairly new state. A shiny memorial centers a traffic circle in downtown Windhoek, the capital (Figure 2). This memorial hosts a museum and is fronted by a friendly waving statue of Sam Nujoma, the country’s first Prime Minister. Nujoma was a member of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), a political and military force that fought and strove for Namibia’s independence and—much like the African National Congress—has steadfastly remained in power ever since. SWAPO has won every election since Namibia’s independence. SWAPO’s first female presidential candidate, Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, prevailed in the 2024 elections.

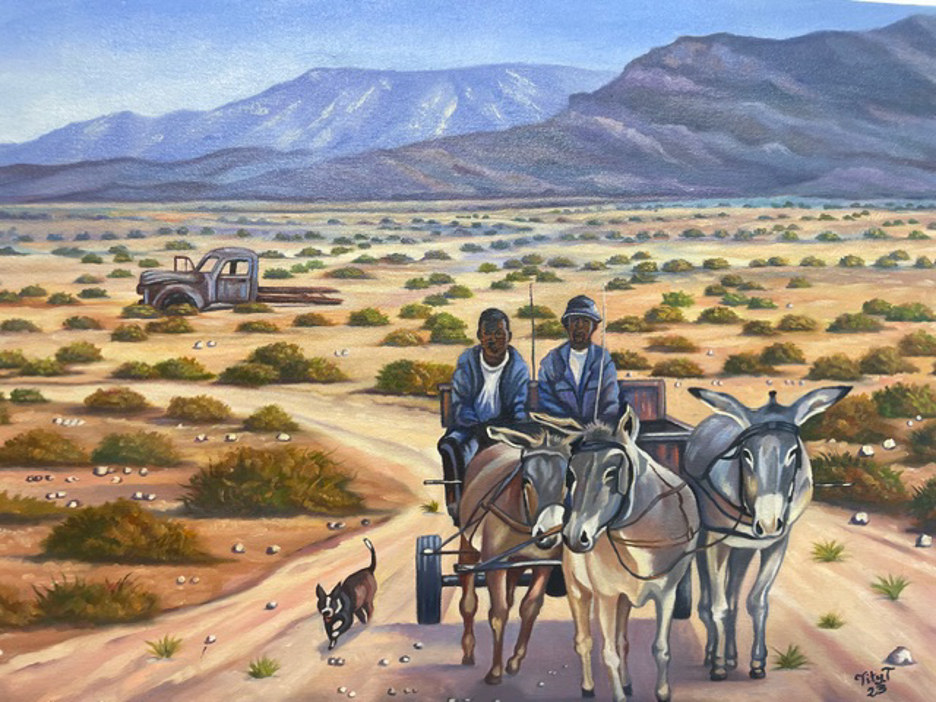

Namibia’s population is roughly three million people. This puts Namibia among the most sparsely populated countries in the world, second only to Mongolia. The name Namibia, colloquially referred to as Nam, derives from the Khoe word Namib, which means ‘vast place’. And Namibia is indeed vast. It is brown, endless browns, browns over smooth hills and jagged rocks, undulating browns, carpets of browns in a dance with a green pointillism, like a Seurat painting, dots of green spots of bush and brush and scrub that while not lush still punctuate all the browns. Namibian art, much of which is inspired by desertscapes, delivers these reductive colors in beguiling fashion. We saw a number of stunning paintings in the National Gallery of Namibia, in the center of the capital Windhoek (Figure 3).

Namibia’s history itself is punctuated throughout by violence, forward-lurchings and backwards-jumpings, a zig-zag arc, and a gradual disintegrative downslope of South African control of the country throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Antecedent German rule over Namibia was not for too long – 30 years, roughly – but these three decades proved extremely poignant. Among the most painful parts of Namibian history is the genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples orchestrated by Germany between 1904 and 1908. Many see this as the first genocide of the twentieth century. We see it similarly. Indeed, we thought about this while we were at the 2025 International Association of Genocide Scholars Conference, which was held at the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Center in October 2025. Keynote speaker Professor Puleng Segalo referred to the Namibian genocide as among the most understudied and underappreciated and underrecognized genocides.

The first German missionaries arrived in Namibia between the 1820s and the 1840s. Beginning in 1904, following a January uprising led by Herero chief Samuel Maharero against colonial rule, German officials ordered the extirpation of the Herero and Nama. On October 4, 1904, German military commander General Lothar von Trotha – the ‘Great General of the Mighty Kaiser’ — issued a chilling extermination order (Vernichtungsbefehl) to his troops: ‘every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people or I will let them be shot at.’ While von Trotha muted his words somewhat in a further order to spare women and children [Writing Namibia, p. 257], the violence remained eliminationist. Water supplies were poisoned. Concentration camps were set up. Germans murdered 10,000 Nama (half their population) and 65,000 Herero (nearly 80 percent of their population), as well as thousands of other indigenous peoples, including the San and the Damara. Some estimates suggest higher death totals – 20,000 Nama and 100,000 Herero, respectively [Writing Namibia p. 221-222]. The surviving Herero were expelled into the waterless Omaheke region, where thousands died of thirst. Those who survived this second wave of extirpation were subject to detention, dispossession, deportation, and compelled labor.

In 2021, German and Namibian negotiators finally arrived at a ‘reconciliation agreement’ concerning these atrocities. Germany apologized and recognized the violence as genocidal, agreeing to pay Namibia €1.1 billion in community aid over a period of 30 years. Among this total, €50 million have been set aside for research, remembrance and reconciliation projects; the remainder is to go to the development of affected descendants’ communities. But the Herero and Nama peoples were never part of the negotiations. They were presented the final text of the deal, conducted between the German and Namibian governments, which was couched as development aid and not as reparations. Germany insists there is ‘no legal basis for individual or collective reparations towards descendants of Ovaherero and Nama people affected by Germany’s colonial genocide’. This is akin, no, to recognizing harm and clouding remedy? Turning to Namibian courts, litigants have challenged Nama and Herero exclusion from this agreement. The status of the agreement remains contested; no funds have been distributed thus far.

Cemeteries, Silences, and Remembrance in Okahanja

The 1904 Herero uprising was crushed. The town of Okahandja, the site of uprising, is today a site of memory. We visited on a sunny Saturday morning. Okahandja is about an hour’s drive north of Windhoek along a major and modern highway flanked by wildlife – including antelopes, ostriches, and monkeys. It’s a small town, home to an old train station with a faded and failing verandah, a brick microwave telecommunications tower, two woodcarver markets and several foodserver restaurants, and a far-from-faded German footprint. Okahandja is the administrative center for the Herero people. Herero Day is celebrated annually in Okahandja, on the day Herero chief Samuel Maharero’s body was buried with his ancestors’ in the town’s Herero cemetery. The name Okahandja means the place where two rivers flow into each other. Namibia, however, is an arid space. These rivers run dry for most of the year.

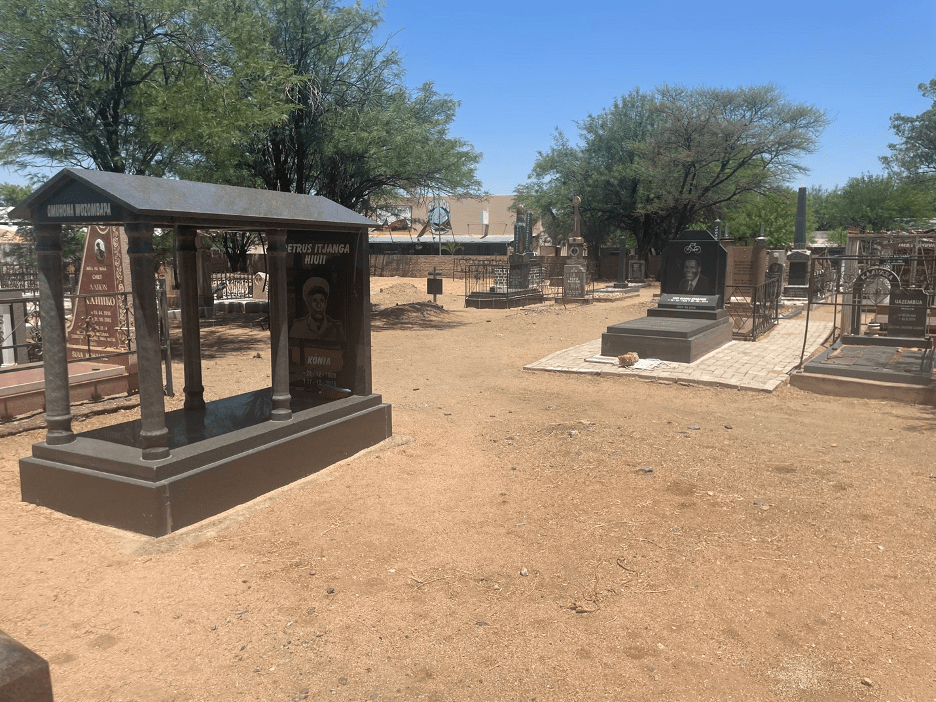

German vestiges persist, including in many street names in Okahandja, and even more so in Windhoek. The Okahandja soil, however, uniquely cradles the bodies of German soldiers who fought in the wars between 1904 and 1908 against the Nama and the Herero. The wars were ugly, and the Germans were coldly and cruelly ruthless. But the bodies of their fallen remain, in graves still tended to and open to the public. The bodies, ensconced in the German Military Cemetery since 1904, lie next to the remains of Okahandjans of far more recent times, including contemporary Herero tribal leaders. The site is anchored by the Rheinische Missionskirche (Figure 4). Two German graves remain unnamed, while the others have detailed headstones (Figure 5). An old German fort, too, sits around the corner. A separate cemetery for Herero chiefs is a few blocks down the same street (Figure 6). It contains the graves of Samuel Maherero and some other Herero chiefs, including Hosea Kutako, founding member of SWAPO and eponym of Windhoek’s international airport. The chief’s graves are locked up and sequestered, not visitable even though signposted, off in a distant fenced field. A small child wanted to take us to see them, behind the fences and locks, but we declined. It didn’t feel right.

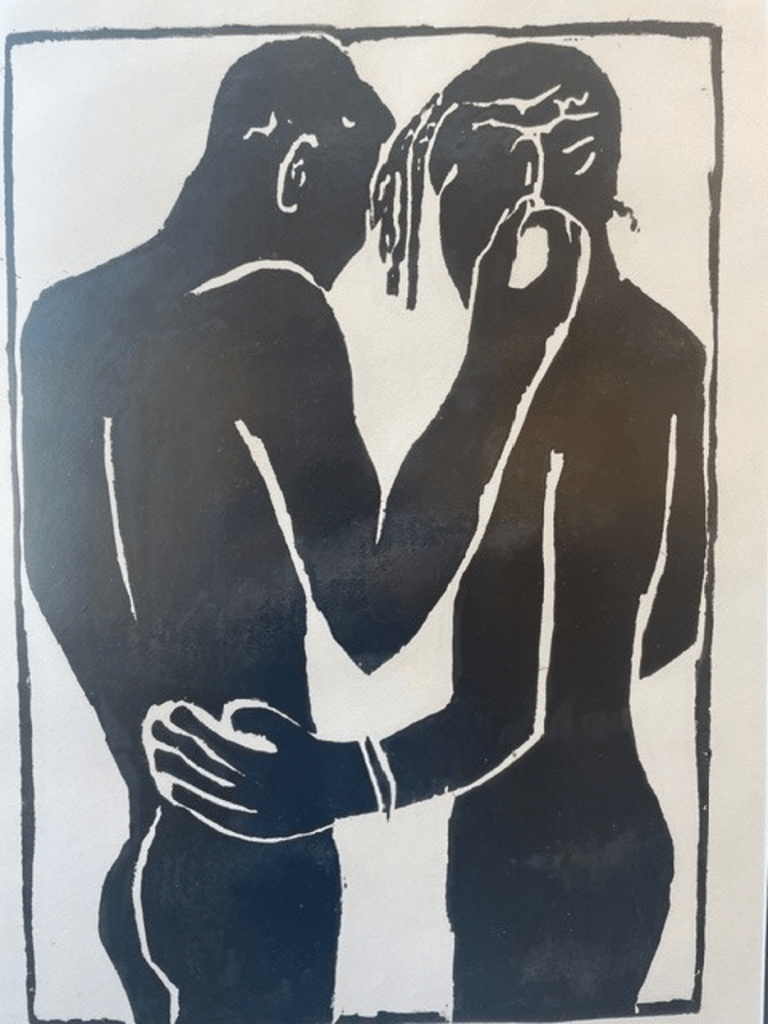

Kintsugi is a Japanese artistic tradition of repairing broken pottery and porcelain by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer while leaving them visible and incorporating rupture into the form. The object is not discarded, nor a new one created to replace. Rupture becomes wrinkle and unity. As an approach to life, kintsugi approaches past breakage as part of the present, not to be hidden or disguised or fretted over. The German Military Cemetery in Okahandja forms a kintsugi of sorts: divided as it is with the German graves on the left and the Herero graves on the right, yet mended together, as one, one side older and the other side newer, with an unmarked yet discernible line in between (Figure 7). The past subsumes into the present, and while scarred, kintsugi imagines it will grow a more just future. This requires care and commitment, gentleness and mettle, recognition and contrition, patience and perseverance. On the morning of our visit we felt a tenderness to the German Military Cemetery’s kintsugi: tenderness among the dead cradled together in the earth, side by side as neighbors of sorts, resting next to each other, the oppressed volitionally placing themselves next to their oppressors, not breaking but joining, together albeit with a seam, across generations. We found strength in this tenderness, like in the tenderness woodcutting we saw in the National Gallery of Namibia (Figure 8).

We found Moordkoppie in Okahandja as well (Figure 9). This blood and death hill, representative of Namibia’s rocky desertscape, is where the Nama and Herero attacked each other. On August 23, 1850, at Moordkoppie, seven hundred Herero were killed by the Nama. It is reported that after the massacre the women’s arms and legs were amputated in order to more easily pillage their copper bangles. Moordkoppie is entirely unmarked and unannounced. It stands silently adjacent to a major highway, and is only recognizable geologically. In an important historical turn, the Nama subsequently joined the Herero in jointly contesting German rule. Samuel Maharero urged solidarity and resistance in a letter to Nama chief Hendrik Witbooi, imploring ‘let us die fighting!’

Sign Posts and Street Names

Despite the genocide, attempts in Namibia to remove colonial names of places have achieved limited success. As we wandered through the streets of Windhoek, the street names were striking. These names form an eclectic global potpourri. Robert Mugabe intersects Nelson Mandela. Fidel Castro and Florence Nightingale are recognized. Some street names are arranged by ‘expertise’. Scientists, for instance: Roentgen, Salk, Curie; our hotel was on Louis Pasteur Avenue. Composers abound – Mozart, Wagner, Strauss, Brahms. Not all street names are German, but many certainly are, such that German characters disproportionately dominate. German colonial authorities determined that any Namibian place names that were ‘difficult to spell for Germans’ should be renamed. Often times, the current street-names are followed with the German ‘strasse’, e.g. Beethovenstrasse, even though the country’s official language is English (Figure 10). Smatterings of Afrikaans remain, as well: Voortrekker Street intersects (the German) Bahnhof Street in Okahandja (Figure 11).

Figure 11 (right): Street Signs, Okahandja, October 2025

To be sure, the scope of the German footprint, while far-from-faded, certainly is shrinking. Some of the streets in Windhoek were renamed shortly after independence, with little to no opposition. So, too, elsewhere. For example, the electoral unit known as the Lüderitz Constituency, named after Adolf Lüderitz, the founder of Deutsch-Südwestafrika, was renamed in 2013 to !NamiNüs. This name, which uses characters from the local Khoekhoegowab language, was what the Nama tribe called the area before the arrival of the German settlers. Germany, too, has changed its own colonial footprint. In 2022, Lüderitzstraße—a street in Germany’s capital Berlin—was renamed Cornelius-Fredericks-Straße in honor of a leader of the Nama people who had fought against the German occupation and was killed in a concentration camp in Lüderitz in 1907.

In light of the absence of a national strategy in Namibia, renaming campaigns faced substantial challenges. One is that some places have different names in different African languages spoken in Namibia, so a reversion to an indigenous name can only acknowledge one indigenous group as among many. Between the influence of German colonialism and the multiplicity of indigenous languages, place names have ended up misspelled in official records, and there are disagreements about whether and how to correct the names. Another challenge is that, while there is a tendency to want to rename places after national leaders, political discord understandably arises regarding who constitutes a national hero worthy of such an honor. Some Namibians, moreover, resist change because of the impact it could have on their businesses, including German tourism, and would rather see resources go toward developing infrastructure. Based on this kind of pushback from local residents, the major town in the !NamiNüs Constituency retained its acutely colonial name of Lüderitz.

The lingering German footprint in Namibia’s public spaces reminded one of us of other approaches to painful histories, for example the architectural and commemorative remnants of Mussolini-era fascism in contemporary Rome and Naples, and the notion that strength may not only lie in scrubbing the ugly visualities of the past but, rather, in just leaving them and repairing onwards and upwards and around and about, thereby invoking a sense of a nonchalant integration in the face of cruel gazes. But for the other one of us, a parallel to memorialization of intra-state repression may not be apt. Colonial vestiges in Namibia linger not only in the names of towns and streets. While German Namibians now make up a mere 2 percent of Namibia’s population, they own about 70 percent of the country’s land (largely used for agriculture). Non-resident Germans also own land. As Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe says, ‘[w]hiteness is at its best when it turns into a myth. It is the most corrosive and the most lethal when it makes us believe that it is everywhere; that everything originates from it and it has no outside.’ The ubiquity of the street names in Windhoek and Okahandja, and starkly uneven patterns of land ownership and use, suggest that the vestiges of colonialism are not just vestiges, but rather remain everywhere, with little to no ‘outside’. Mbembe’s native Cameroon, like Namibia, once existed under the boot of German colonialism.

The land-ownership question is raw and deeply inter-generational [Writing Namibia,pp. 276, 282] for Namibians. While the genocide of the Herero and Nama assuredly had a racial animus [Writing Namibia,p. 255], it also had an economic animus in land and cattle ownership. For the Herero and Nama to be dispossessed of land, and cattle, and for the control over land and ownership of cattle to pass into settler hands, evidences a painful evisceration of identity, community, and economic sustainability which also forms part of the eliminationism of genocide [Writing Namibia p. 108]. Genocide in Namibia occurred as part of a violent colonial capitalism [Writing Namibia p. 109]. Racism was a central thread, assuredly, but it was not the only thread. In a sense, these stark disparities in land ownership prolong the 1904-1908 genocide.

Nujoma rued the time it took for Namibians to come together to face the colonial adversary [Writing Namibia p. 103]. Despite their collective resistance against the Germans, divisions remain today. The Herero and Nama—ethnic minorities within the country—find themselves at the periphery of Namibian society and express skepticism about the legitimacy of the Namibian state [Writing Namibia pp. 114, 217]. Decisions over street names, let alone land, may lie beyond their reach.

Concluding by Looking Ahead

What to do with the promised 1.1 billion Euros? This is something the two of us chatted about.

A museum, one of us suggested. And indeed this is a way to officialize and recognize genocide. Memorialization is present in Namibia, including in Windhoek, but not in Okahandja. There is also a Nama and Ovaherero Genocide Memorial site on the Shark Island peninsula near Lüderitz. In Swakopmund, by the sea, a genocide museum was established in 2015. Germany should also return Namibia’s cultural heritage, some of which remains in its own museums. Germany has returned some artifacts pilfered from Namibia during colonialism, as it has with other former German colonies in Africa. It has also repatriated some of the remains of Herero and Nama people that were sent to Berlin for scientific ‘research’, intended to prove the supreriority of Europeans. But Germany still possesses remains and other material goods from colonial and genocidal pursuits in Namibia.

Factories, the other replied? Create work and build cars? We noted many factories on the highway from Windhoek to Okahandja. Perhaps there could be even more. Perhaps factories matter more than museums. Some descendents of genocide survivors have argued that the Germans are obligated to build schools to educate their children. [Writing Namibia, p. 276]. But what many seem to want, especially Herero survivor families, is to address the issue of lost ancestral land. One Herero elder has suggested that the German government should buy land back from German landholders in Namibia and return it to the descendants of those who lost it during the genocide [Writing Namibia, p. 279]. The return of land, for some descendants, would be a way for Germany to acknowledge the dignity of the Namibian people:

With what they did, they must come down to earth. They must come to pay these people whom they made whom they are today. They must come to rebuild the country in the areas which they know that these people that they killed are living. If they are really believers in God or if they are human. They must come back to build the dignity of these people. [Writing Namibia, p. 280]

What is the operational difference between development aid and reparations? This is a contested point in Namibia, as Germany has refused to acknowledge any obligation to pay reparations. German approaches to Namibia contrast with German approaches to Israel in terms of the invocation of reparative language for historical injustice.

Participation, too, matters. Who stands in the frame and who remains outside of it? Should inter-state agreements include non-state actors, like the Nama and Ovaherero communities? Land ownership is also a crucial topic, given the endurance of German control over the majority of Namibia’s land. And time, notably, the serendipity of timing, this too matters as among mirrors and windows. The stark limits of law – rooted as it is in non-retroactivity – surface insofar as the term genocide did not exist in 1904, or 1908, and, hence, the formal recognition of the violence as genocidal hits a temporal snag. Germany can call it genocide, and it does (Völkermord), but this categorization does not trigger preventative or reparative responsibilities since no law existed at the time to mandate remedy. This is a historian’s genocide, not a lawyer’s genocide. Hence, the ‘development aid’ emerges not out of obligation or responsibility or entitlement, but, rather, out of charity and volition. It remains to be seen whether tenderness and recognition can carry Namibia, the Nama and Herero, and Germany into a more just future.

[1] Mark A. Drumbl and Shannon Fyfe, School of Law, Washington and Lee University. Thanks to Carlyn Kirk, Barbora Holá, and Jeremy Thompson for their insights. All photographs in this essay were taken by the authors.